CRAFTLINES

AUGUST 2015

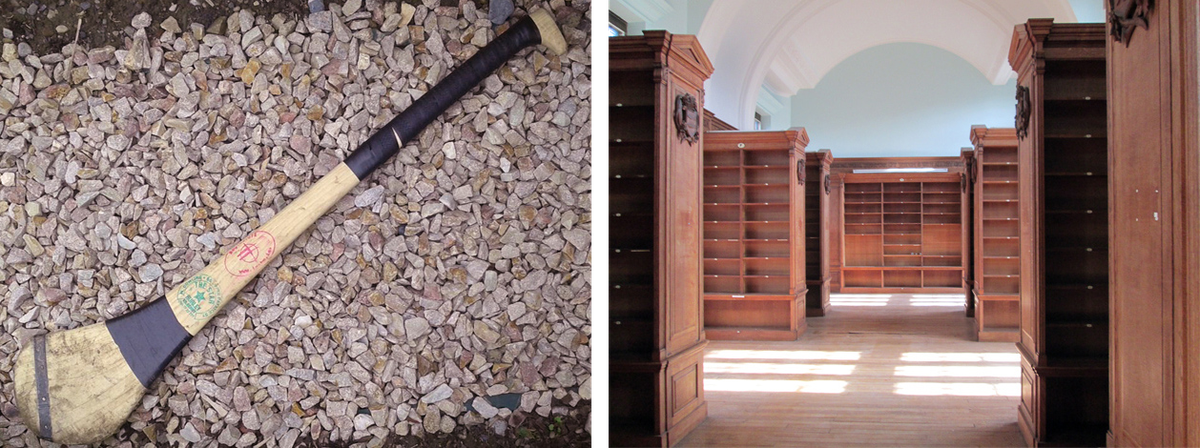

My grandfather has worn many hats; soldier, civil servant, father of seven, husband, and winner of a county final in hurling (the achievement of which he is potentially most proud). He is fluent in Irish and recalls event and dates from 50 years ago with a staggering accuracy. Yet the residing image of him from my childhood is as a craftsman – in the garage next to his house in Dublin, whittling and sanding a piece of ash to form a hurley, sizing it precisely for the user, wrapping the handle to create the perfect hold. I remember sitting, playing surreptitiously with a clamp, watching this in awe: the creation of the perfect instrument from a piece of timber; a skill honed through practice and an unfailing attention to detail. I marvelled at the assurance of it all, the promise in his hands.

It would be satisfyingly simple to attribute my choice of career to these moments – to claim there was an epiphany in watching him, a sudden realisation that I wanted to be an architect, to create. In reality, however, the path was not so linear; instead the conviction that I wanted to become an architect embedded itself in my consciousness slowly, over time. The memory of him working in his garage was one I didn’t return to often, and like any story we fail to repeatedly tell ourselves, it languished, dormant, in the recesses of my mind.

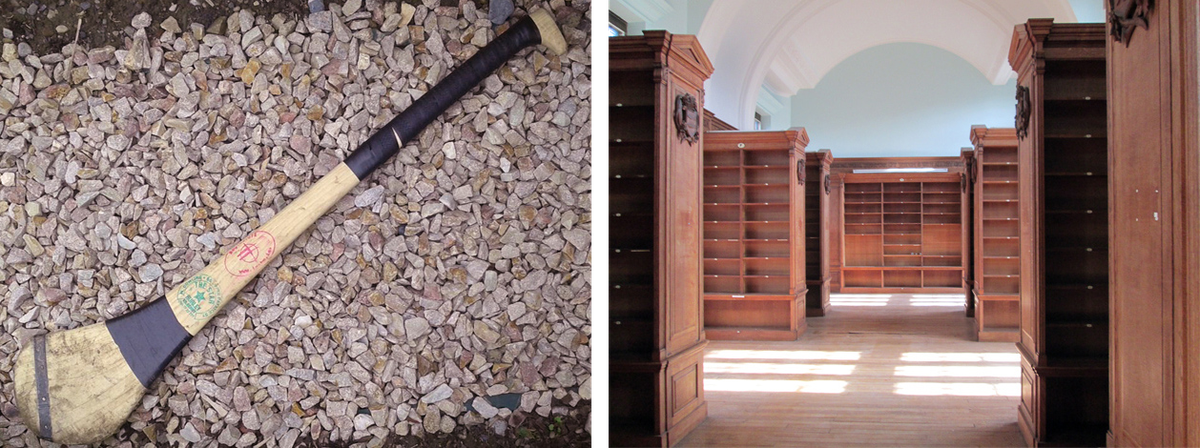

I recently went to site at Jesus College, Cambridge, where we are working on a project that is part new build, part refurbishment. An aspect of the refurbishment involves the adaptation of eight bookcases in the magnificent former library into wall panelling. The existing bookcases are a dark stained timber, designed by Maurice Webb in the 1920s and wonderfully crafted by a masterful hand. Reworking these without compromising their beauty would be a challenge for any craftsman.

On seeing the work the joiner had done, I realised there was no cause for worry – it had been executed with confident, competent hands. In that moment, the memory of my grandfather in his garage came back to me in glorious Technicolor; and I felt a familiar thrill at the embodied potential of the right material in the hands of a craftsman, with promise in his hands.

FRAMELESS ARCHITECTURE

AUGUST 2015

Our classification of the world is the result of a desire to impose order on the chaos we are born into. In nature we classify the species, in society we classify our relationships, and in architecture we classify the spaces we design and inhabit. In many cases, classification is a useful tool that allows us to root ourselves in time and space.

Classification can also be the enemy of imagination, suffocating our desire to wonder and discover new associations. It can limit the understanding of what surrounds us and disjoint elements that should not be separated. Framing perception can become a reductive force.

In his book Atlas: How to Carry the World on One’s Back, Didi Huberman uses ‘atlas’ in its broadest sense to mean a ‘collection of images’. Huberman explores two different ‘uses of reading’: a denotative sense in search of messages, and a connotative sense in search of montages. The dictionary is a predictable tool for the former, and the atlas is the ‘unexpected apparatus’ for the latter[1].

The atlas is frameless and endless. It surpasses boundaries and restrictions and is in a state of constant renewal. The atlas enables our imagination to trigger new associations, new relations. Although we may start with a search for the specific, we may then wander endlessly, unlimited by a defining frame.

Architectural education, architectural research and architectural practice have suffered for too long from being limited by a defining frame that has placed them in different dictionary entries. It is now time to rethink this model, which shapes our lives, our careers, and ultimately our contribution to society. If we are to replace the dictionary with the atlas, if we are to substitute the definitive meaning with the endless search for new relations, we will have a new model of architecture where education, research and practice are interwoven and intrinsic to one another.

For this new model to succeed, we must completely awaken our imagination. Education, research and practice will be symbiotic and won’t be understood without each other. As a result, transverse readings and meanings will develop within our work. These will be found not only in the individual but also in the collective. In our office, inspired by Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, we will develop our own Atlas where images of our endlessly evolving inspirations and aspirations will be captured. Our Atlas will be a new ground from which meaning, space and relationships will grow. Our Atlas will enable us to read what has never been written[2].

[1] Georges Didi-Huberman (2010). Atlas. ¿Cómo llevar el mundo a cuestas?. Madrid: TF Editores/Museo Reina Sofía . 16-17.

[2] Georges Didi-Huberman (2010). Atlas. ¿Cómo llevar el mundo a cuestas?. Madrid: TF Editores/Museo Reina Sofía . 14.