Lightenings - Architecture Today

Issue 237

April 2013

Text Mary Ann Steane

Images Dennis Gilbert

A concern for light has always been central to Níall McLaughlin’s architecture. In a sense he sees himself as building with light, and yet is aware, more than most, that a search for light needs to find a telling concept if it is not to be read as a merely escapist effect.

At the Bishop Edward King Chapel at Cuddesdon in Oxfordshire, McLaughlin had an unusual brief. The building not only forms the central gathering place for Ripon College, a major Anglican training centre, but is the permanent legacy of the small religious order at Begbroke, the sisters’ generous gift on joining their larger neighbours.

A powerful narrative has stimulated many aspects of the design, one that ties the project to the site as it touches on light’s fundamental role in spatial orientation. Taking its cue from the Seamus Heaney poem ‘Lightenings VIII’, the chapel recalls the miraculous ship of the upper air whose anchor hooks the altar rail at Clonmacnoise. At Cuddesdon, the vessel is snagged by the tangled branches of the huge trees that form a leafy backdrop to the college entrance.

The word ‘nave’ stems from the Latin ‘navis’ – ship – and boats are a common symbol in Christian architecture: Noah’s Ark and the medieval ‘ship of souls’ spring to mind. As a metaphor, the ship tellingly embodies the collectivity and interdependence of a community, but what has it to do with light?

Permanence and ephemerality – what is weighty and what is weightless – are held in tension in this project. A primary gesture of grounding initiated the design process when McLaughlin first impressed his thumb on a plasticine model of the hillside site. Within a rigorously simple volume of loadbearing stone located by this gesture, a soaring armature of timber is inserted. This structure not only helps contain the action at the lower level in a fluid orchestration of space and movement, but draws the eye upwards, capturing and filtering the natural light. On a sunny day the upper surfaces become an animated embroidery of light and shadow in tune with the surrounding windblown foliage, but even on a dull day the way that light is held within the tall enclosure is critical to the project’s narrative of tethering.

Concern for the marriage of geometry and surface lead to a spatial resolution in which the centre line of the ceiling, the junction at which the complex timber structure and simple plaster soffit gently meet, becomes the ship’s keel. The idea dawns that not only are we in the ship, gathered amongst its masts, but at the same time submerged in the womb of the sea. We are thus not in the light but definitively below it. And suddenly, unexpectedly, the light above us acquires depth.

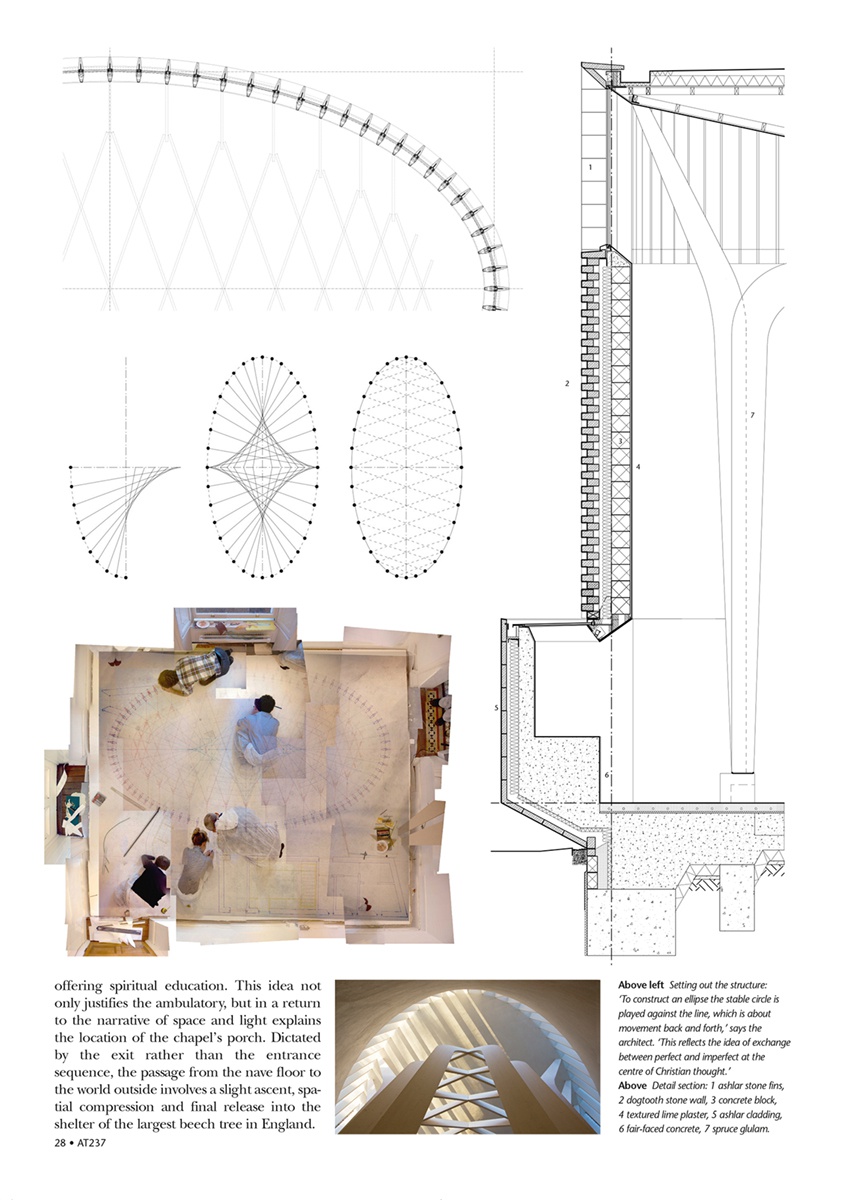

According to McLaughlin the building’s elliptical form was directly inspired by the 1954 Rudolf Schwarz chapel of St Michael in Frankfurt-am-Main. Beyond its capacity to evoke a ship, he uses it here to qualify formality with informality while staging deft critical adjacencies, separations and alignments. An ellipse whose foci mark the positions of altar and lectern, and which contains the two lines of facing seats that are traditional in college chapels, is extended by the entrance porch and three smaller enclosures which protrude off-axis from its base: a seating area for the sisters, an oriel window whose distant view across the rolling landscape brings an unexpected moment of colour and depth, and the tabernacle niche. This arrangement means all members of the congregation can see the altar, with the sisters close by, aligned with the tabernacle beyond, and the college’s ordinands closer to the lectern and its sermons. Unlike the Schwarz chapel, the structure supporting the roof is on the inside. Not only does the resulting screen of columns contain and measure the moment and place of gathering, but it disperses sound well enough to prevent the poor acoustics that can dog curvilinear churches.

Gottfried Semper’s explanation of the origins of architecture in ancient rites and crafts was a major influence on the project’s material vocabulary. Thus, the altar/hearth forms the nucleus around which the community meets while, as Semper suggests, a heavy concrete mound, an enclosure of ‘woven’ stone and a carpentered roof articulate its transaction between earth and light. The argument is particularly clear on the exterior. Constructed in Clipsham stone, and with approximate proportions of 1:2:1, an ashlar base supports a deeply modelled tapestry of alternately smooth-faced and rough-faced blocks below a ring of clerestorey windows. At the top, the spacing of the daringly slender stone mullions is carefully attuned to the lightweight ‘open-work’ of timber ribs within.

These bands reappear on the inside. The walls pass from flatness to a kind of tumult: the lower region is smooth lime plaster, the middle region rough lime plaster, and the upper region a finely wrought interlacing of windows, mullions and ribs that evokes the turbulence of the waves below the miraculous ship. Here everything is washed with white – structural timber, furniture, walls, ceiling – but for the pale grey floor, and the bright gold of the tabernacle interior and the lamps that hang from the ceiling, mediating between the worlds above and below. At the nave’s southern edge, narrow slot windows offer further seats and glimpses outwards.

The slight depression of the nave creates an unusual setting for worship in that its linear concentric geometry more obviously recalls a medieval moot, a place of debate, than a church. Such debates sometimes took place in natural theatres in the landscape like woodland glades; as the chapel at Cuddesdon seeks to build a relationship with the trees, perhaps this reading is apt. McLaughlin notes that ‘nave’ is also the term for the hub of a moving wheel, and thus a powerful metaphor for an institution offering spiritual education. This idea not only justifies the ambulatory, but in a return to the narrative of space and light explains the location of the chapel’s porch. Dictated by the exit rather than the entrance sequence, the passage from the nave floor to the world outside involves a slight ascent, spatial compression and final release into the shelter of the largest beech tree in England.

Another motif borrowed from Seamus Heaney, the figure of the kite-flyer, a man caught up in his task, eyes on the empyrean but with feet planted on the ground, arms straining against the wind, helps explain how McLaughlin builds light. This is soaring yet earthbound architecture, which eloquently reinterprets tradition so that everyone and every element finds its place. This chapel is also a building whose orienting dialectics of site, light, depth and distance distil an argument concerning the human soul out of an eye-catching visual spectacle. A building, therefore, whose light symbolism will become more powerful over time as its lower reaches acquire the patina of age. Seamus Heaney once said: ‘If poetry and the arts do anything, they can fortify your inner life, your inwardness.’ In this remarkable project, McLaughlin shows us how.