A Lifetime of Renewal - Architects' Journal

July 2015

Text Niall McLaughlin

The practice of architecture must be understood as an independent discipline with its own ways. It is a mistake to think of it as something that is defined by the criteria of the profession or the schools, which, as institutions, will seek to shape it by defining it in relation to their own norms.

The quid pro quo between government, profession and schools is historically conditioned. It came about during the 19th century, when membership of a professional institute became established as the benchmark for architectural competence.

Within this context, I would like to address the frequent question about what are sometimes referred to as ‘oven-ready architects’. That is the requirement for schools to concentrate their teaching on the acquisition of certain skills that are deemed necessary by the profession. At any given time, this could be drawing, construction detailing, legal compliance, BIM or making digital images. Architectural practices call for core ‘employable’ skills to be prioritised, while schools often insist on their primary vocation as liberal research academies. The professional institutions seek to balance these demands through exhortation, awards and prescription.

As a result, we witness a polarisation between professional practice and schools that is focused on a clash between competence and values. Top schools often employ a majority of teachers who deliberately position themselves far from the norms of mainstream practice and their students produce relatively conceptual projects, often gloriously illustrated, that are commonly interpreted as a challenge to the values, ethics and competence of professional practice. Not unusually this year, at the Royal Gold Medal Crit in the RIBA, one of the Gold Medal recipients felt unable, or unwilling, to offer any comment on the work of the winner of the student Silver Medal.

From my own experience as both a teacher and a practitioner, I can’t deny that a condition of alienation exists between many key schools and many professional practices. There is an entrenched, polarised difference about what constitutes proper standards, values and competence and who holds the responsibility for preparing candidates for a life of architectural practice. It is a difference often typified by mutual incomprehension.

This difference is based on a misunderstanding about the proper place for education and the proper place for practice. The accepted model envisages a student spending five or seven years of education ‘warming up’ for the practice of architecture and then carrying their acquired skills and values out of academia like water cupped between their hands, which then spills through their fingers when they encounter the disappointments and harsh realities of practice. This is an impossible construction, which is fundamentally flawed in its separation of education and practice.

I insist that practice begins when you enter into architecture at the commencement of training. Academic projects should be not merely a dry run. Schools owe it to society to constitute a form of practice that is both engaged with problems and opportunities in the world and also free of the more exacting demands of professional work. Those teachers who do not build engage in a form of architectural practice through writing and drawing that can stand beside the activity of building in the broad discipline of architecture. The documents, texts, drawings and projects that they create should shape debates for those of us who build.

Education should not end with RIBA Part 3, or even limp along through minimum prescribed CPD events. It should no longer be possible for an architect to finish their education. I propose a more comprehensive model of life-long learning. If practitioners return to education throughout their careers, they will be constantly invigorated and, by extension, so will the schools to which they return. This would constitute a discourse – in the sense of a ferrying back and forth – in which practice and education are both part of a seamless continuity.

The key to my argument is that the purpose of education is not so much the acquisition of set skills but – to borrow a phrase from John Hattie – learning how to learn. Once you have done this, you have built an engine for a lifetime of renewal.

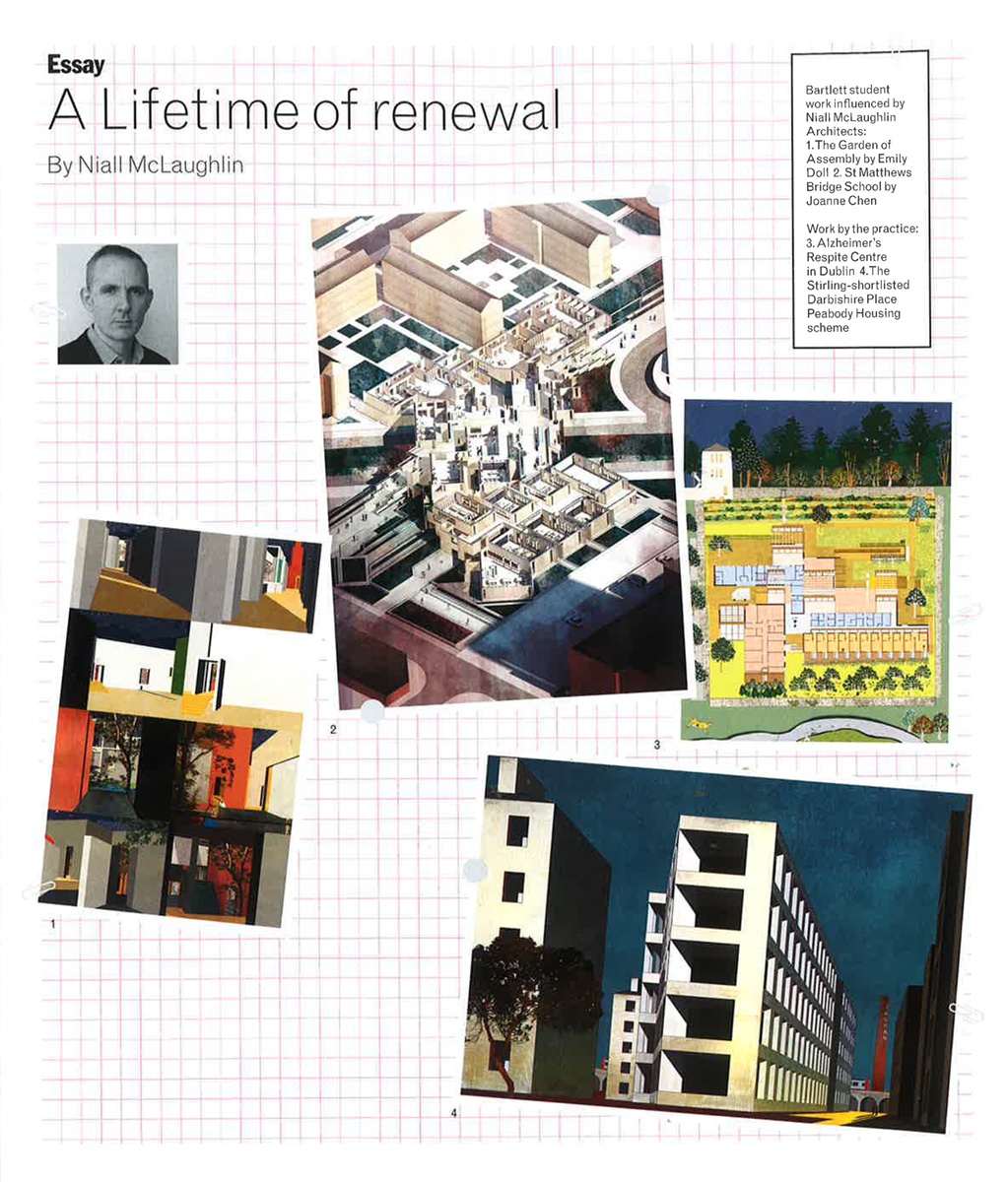

How is this carried out in my own teaching and practice? I approach teaching as a second education for myself, attempting to connect the forms of practice possible in a school with the practice of building. I teach at the Bartlett with my colleagues Yeoryia Manolopoulou and Michiko Sumi in a small unit of about 15 students and each year we try to address an issue from contemporary society which might impact upon the way in which architecture is understood. This year, for example, we looked at the impact of devolved powers to British cities and asked ourselves whether a new kind of public representative architecture might be possible in the light of these planned political changes.

To extend the reach of the unit beyond the immediate confines of the school, we are forming a mutual, collaborative group of ex-students and colleagues, all now with their own emerging practices, who exchange information and critically review each other’s work. We will use meetings and common digital platforms. Our members will return to review and mentor the current students and, in return, they will be challenged by the student’s aspirations and expectations.

The school is therefore somewhere for everyone to come back to. This collection of emerging practitioners will form a co-operative long-term network constantly re-educating each other.

Working in our architectural practice involves committing a proportion of your working time to dedicated research and reflection on issues emerging from our building activity. Everybody is asked to pursue a subject that can add to the body of knowledge within the practice and beyond it. We come together to evaluate our impact through all of our labours and errors. These structures of teaching, building and reflecting make a network of lifelong education and practice that is critical, mutual and social, and which recirculates between education, speculation, construction and inhabitation.

I propose that education and practice should occur in parallel throughout our lives in architecture. From our first day in school we should believe in ourselves as practitioners, influencing the world through our production. Until the very end, we should continue to educate ourselves and engage openly in speculation. We should do this by understanding that education is not merely the acquisition of facts and prescribed skills, but developing an inner compass that always points in the direction of further education. By achieving this, our practice is endlessly refreshed.